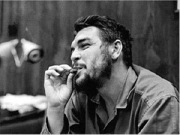

In the decade that has elapsed since I wrote these recollections, the world has changed again. Being a foreign correspondent is now a more dangerous and compromised profession than it was in 1967. The events I describe are now seen through the prism of books and films that in themselves re-shape our understanding of the past. Che Guevara is now seen, even by those who were his sworn enemies, as a romantic revolutionary, more Lord Byron than Lenin. An American diplomat (speaking at an Internet conference in Chile, just two weeks before Wikileaks flooded the world’s press with the private musings of US ambassadors) described the Internet as “the Che Guevara of the 21st Century”. I have tried to be as faithful as possible to the events as I lived them.

Looking back 33 years to the summary execution of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara in the dry scrubby forests of Eastern Bolivia, it is almost impossible not to be influenced by subsequent events, by profound cultural and political changes that have swept through the world. Guevara was killed a year before the upheavals of 1968 which sent tremors through the capitals of North America and western Europe, destroying the presidencies of Lyndon Johnson and Charles de Gaulle, a year before the short-lived Prague spring.

Latin America barely figured in the news pages of the British press and it hadn’t yet become a popular destination for back packers or students in their gap year. Cocaine was still an exotic substance that barely registered in my consciousness when I was sent to take over the Reuter office in Lima in September 1966. Guevara had made the front pages when he resigned from Fidel Castro’s revolutionary government in 1965, but his movements were a minority interest. President Kennedy’s ‘Alliance for Progress’ seemed to have contained the threat of rural insurrections of the kind that had led to the overthrow of Fulgencio Baptista in Cuba 10 years earlier.

All that changed in early 1967, when another ex-Reuter journalist, Murray Sayle, a larger-than-life Australian, took time off from covering a round-the-world yacht race for the Sunday Times to visit land-locked Bolivia. He broke the news that a guerrilla encampment had been discovered near Camiri, a tiny oil town so remote that by scheduled flights, it would take three days travelling from Lima, via La Paz and Santa Cruz. The Bolivian government claimed that they had uncovered the headquarters of Che Guevara’s ambitious plans to launch a continental guerrilla army.

It seemed utterly far-fetched. The consensus of Lima-based foreign correspondents was that General Rene Barrientos, Bolivia’s military ruler, was simply using the story to squeeze more aid out of Washington. No one took very much notice until the Bolivians produced their prize exhibit, Regis Debray, a young French intellectual, who had been recruited by the Cubans to publicise the Latin American revolutionary struggle. A year earlier, he had published a pamphlet in Havana, “The Revolution within the Revolution”, which laid out Guevara’s belief, contrary to Soviet orthodoxy, that the foundations of the Latin American Revolution had to be laid in the countryside, supported by the peasantry, far from the corruption of the city.

It soon became clear that the trial of Regis Debray, before four military judges in Camiri, would be a major media event, with a revolving cast of around two hundred journalists from Europe and North America crowding into a town that was totally unprepared to receive them. The wheels of Bolivian justice ground slowly, but once the trial got under way in July, we had to be there. I needed a crash course in the complexities of international revolutionary theory, to understand exactly why the Cubans and the Soviets could be both close allies, yet in total disagreement about Latin America. I had an excellent tutor in Richard Gott, the Guardian’s correspondent in Latin America who was writing a book on rural guerrilla movements.

He already knew the very exotic delegation of international Marxists, who arrived in La Paz under the banner of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, Robin Blackburn and Perry Anderson of the New Left Review, Tariq Ali, former President of the Oxford Union, by then a leading light in one the British Trotskyist factions, and Ralph Schoenman, Bertrand Russell’s American secretary. Schoenman was the only member of the delegation who reached Camiri with press credentials (from a small left-wing weekly). He was not alone in mixing his roles. Among the journalists, there were at least one member of Israeli intelligence, one CIA agent, one Cuban agent and probably others whom we never identified. Others, whom we suspected of such affiliations, were probably innocent journalists.

Keeping the story alive for weeks on end was a real challenge, as the outcome of the trial was never in doubt. The Bolivian military and their allies in Washington wanted to expose an international, communist conspiracy, with Regis Debray and Ciro Roberto Bustos an Argentinian, who had been arrested with him, as the living evidence of the terrorist threat. Debray’s defence was that he was simply a journalist plying his trade. The facts were not in dispute. Debray had entered the country on false papers; had spent a number of weeks with Guevara and his small band of Cuban and Bolivian volunteers; and had been arrested as he tried to leave the guerrilla’s area of operations.

My abiding memory of the 8 or 9 weeks in Camiri is the rare pleasure of idleness without guilt. The court sat each morning for two or three hours; we filed our copy through a special facility set up by Cable and Wireless for the duration of the trial, and then were free to swim in the river, flirt with the local girls, play chess and drink and talk with journalists. Another month and I might have got bored, but I actually remember it with unmixed pleasure. Camiri was, and probably remains, a grid of unpaved streets around a central plaza, with low wood and concrete buildings roofed with corrugated iron. An Italian who had arrived in 1945 and enjoyed excellent relations with the local military ran the only restaurant. We could only guess at his past; it wouldn’t have been polite to ask. The trial of Regis Debray must have been a once-in-a-lifetime bonanza.

One week-end in early October, Richard Gott suggested that I should accompany him to Santa Cruz, where American Green Berets were training Bolivian troops in counter-insurgency warfare techniques. Richard thought rightly that we were more likely to find fresh copy and fresh angles at La Esperanza, the sugar mill where the Americans were based. In any case, Richard was by then working as a researcher for Brian Moser a Granada television producer, who had come to Bolivia to make a film for Granada’s World in Action.

Santa Cruz is the capital of Eastern Bolivia and at that time it was enjoying an economic boom, based on oil, agriculture, and dramatic increases in land values. It was hard to imagine that the poverty-stricken highlands around La Paz and the rich lowlands around Santa Cruz were both part of the same country. Until air travel altered the social geography of Latin America forever in the middle decades of the twentieth century, it had taken less time for a plantation owner in the Beni region of Bolivia to travel to London by boat than it did for him to reach La Paz.

Sparsely inhabited, and tightly controlled by the military ever since the Chaco War, which had pitted two of the continents poorest countries, Bolivia and Paraguay, against one another in the 1930s, South eastern Bolivia was an unpromising seed-bed for a continental revolution. We now know that Guevara had chosen it for two reasons. The first was its proximity to Argentina, the real focus of his revolutionary strategy, and the second was a climate that wouldn’t adversely affect his asthma. He was accompanied by tried and trusted Cuban companions, who had fought with him in the Cuban sierras more than a decade earlier, but neither they nor their Bolivian recruits knew much about the area they had chosen to establish their headquarters.

Sitting over cold beers on Sunday, 8 October, talking over the evident seriousness with which the American special forces viewed the threat posed by Guevara, we were hailed by a sergeant, whom we had met earlier in the day at La Esperanza. “You guys should get down to Vallegrande. They’ve captured Che!” Easier said than done. It was eight in the evening and Vallegrande was around 200 kilometres away over dirt roads. It was hard to find a driver who would take us there that night; they weren’t worried about the guerrilla, but they weren’t keen on carrying foreign journalists through the military roadblocks that we would certainly encounter.

They needn’t have worried; we rolled into Vallegrande in the early hours of Monday. Here was a little town in the rolling foothills of the Andes, even less touched by the outside world than Camiri, which was on a main road from Santa Cruz to Argentina. That morning, however, Vallegrande was buzzing with the news that a battle had been fought between a Bolivian army patrol and the guerrilla. We also learned that operations were effectively directed by two Americans of Cuban origin. We discovered their names by the simple expedient of going to the town’s only hotel and checking the register, Felix Ramos and Eduardo Gonzalez.

We waited most of the day on a small grass airstrip, rumours swirling through a small but excited crowd. Brian Moser discovered that he had only 2 or 3 shots left in his camera and no more film. My main worry was how my story could be filed. Unless I could get the news to La Paz, my rivals would arrive in hired planes and possibly file the story before I could get back to Camiri. However, there had been several false reports of Guevara’s capture or demise, one filed by Agence France Presse just ten days earlier. I had to see Guevara with my own eyes, dead or alive, before writing a word.

In the late afternoon, a small helicopter swirled into view out of the setting sun. As it circled the field, we could see a bundle strapped to one of its runners. Once the helicopter had landed, soldiers prevented our approach, but we saw the bundle loaded into the back of a battered blue van. Our driver, by now as excited as we were, gave chase. We crowded around the van as it stopped in front of iron gates. “Let’s get the Hell out of here!” shouted a burly figure in combat fatigues. He later pretended not to understand English, but he was clearly one of the Cuban Americans directing affairs.

Despite the best efforts of the soldiers, the crowd pushed into the compound, where Guevara’s body was laid out on a slab in the improvised morgue. Richard, who had interviewed Guevara in Havana, was in no doubt that the Bolivians had indeed killed the Argentine guerrilla leader. The black and white photograph of Guevara, lying with his eyes wide open, has been reproduced many thousands of times over the past 33 years. It was almost my first encounter with violent death, and his clear gaze remains fresh in my memory. There was no fear in those eyes. What, I wondered, had he seen in the situation that I couldn’t see? How had he managed to die without being overcome by desperation and despair. The bullet hole through his torso told us that if he had indeed been captured, he had subsequently been summarily executed.

We now know that his execution was ordered by the Bolivian generals, who felt it would have been a blow to their national pride to have handed over Guevara alive to the US forces. This may have been decisive in establishing Guevara as the iconic Revolutionary figure of the second half of the twentieth century.

We didn’t remain long in Vallegrande. For one thing, we were afraid that we might be prevented from leaving the town. We did, however, find a telegraph office, with an operator who tapped out messages in morse code to the telegraph office in La Paz. More hopeful than confident, I sent a one paragraph story to Hector Villegas, the excellent Reuter stringer in La Paz, c/o Cable & Wireless. After leaving Richard and Brian in Santa Cruz, I persuaded the driver to take me back Camiri, where I knew I could find a telex and file the full story. We had by then been awake for around 36 hours but our driver understood exactly what was required. At some point during that long night, we stopped at a roadside bar and persuaded its owner to tune into the BBC World Service: “Reuter’s correspondent in La Paz has reported that Bolivian troops have killed Ernesto Che Guevara, the former associate of Fidel Castro, who resigned his post in the Cuban government in 1965” So my cable had got through and the first hurdle was cleared.

The next day in Camiri, I filed a long piece, which in a unique double appeared under my byline on the front pages of both the New York Times and Izvestia. So what had Guevara seen? I compared his appearance in my piece to a mediaeval painting of St John the Baptist and he became an iconic figure in death for millions who had paid little or no attention to him while he was alive. The 33 years that have elapsed since his death have seen armed revolutionary movements successful in Nicaragua and close to bringing governments to their knees in Argentina, Guatemala, El Salvador, Peru and Colombia.

As I write, the United States is pouring military aid and combat troops into Colombia in an effort to prevent the country slipping out of central government control. Rural guerrillas under the leadership of one of Guevara’s contemporaries, Manuel Marulanda, who have been quietly enlarging their spheres of influence in rural Colombia over the past three decades. It’s just possible that Guevara was more clear-sighted than most of the journalists who mostly reported his death as the final chapter of a revolutionary odyssey.